In our first session of Spycraft Tips and Tricks, we’ll cover a technique that is so simple in nature that it is easily discarded by most yet is devastatingly effective. When overwhelmed in the moment, whether it is being suddenly captured, having the indigenous informant you recruited turn you into the local authorities, or suddenly being shot at from a rooftop, you need something to help you survive the moment. What you’ll learn today can be divided into three separate parts, the last one perhaps being the most powerful, least known trade secret a spy could learn (though these days I’m not even sure they teach it anymore as it is an “old school” technique). But first, we need to understand something called the training matrix.

In our first session of Spycraft Tips and Tricks, we’ll cover a technique that is so simple in nature that it is easily discarded by most yet is devastatingly effective. When overwhelmed in the moment, whether it is being suddenly captured, having the indigenous informant you recruited turn you into the local authorities, or suddenly being shot at from a rooftop, you need something to help you survive the moment. What you’ll learn today can be divided into three separate parts, the last one perhaps being the most powerful, least known trade secret a spy could learn (though these days I’m not even sure they teach it anymore as it is an “old school” technique). But first, we need to understand something called the training matrix.

A training matrix determines the best way to empower an agent to deal with the full spectrum of situations he may encounter in the course of his operations. As such, it look sat what is likely to happen, likely not to happen, and what how much is known about the circumstances. Everything is then divided into the known knowns (what is verified as reality), known unknowns (what we are sure that we don’t know but can speculate probability of), and the unknown unknowns (recognition that shit happens). Our training then becomes divided into three categories to deal with each:

- Known Knowns. Specific procedures precisely geared to deal with the circumstance.

- Known Unknowns. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that are a sort of “if, then.” If situation A happens, then immediately do action B. This is the crux of what is called “foundational” training and encompasses most of the training an agent goes through. (I’ll talk about foundational training at a later time and delve into how present day operators are finally being taught the most solid foundational training through a lot of lessons learned over the past few decades). These are the training drills done over and over that make reactions to situations almost subconscious in nature. It is faster to act than think and almost all situations can fall into the Known Unknown category when operations are mostly “on plan.” However, when things go wrong, we then must learn to deal with…….

- Unknown Unknowns. Training here then involves systematized thinking in that agents need to have an effective approach to problem solving. These are the WTF moments you tell your fellow spy buddies about when you’re 80 years old in a Thai bar over shots of rum. For instance, you’ve been trained to shoot identified suicide bombers on site as they approach your checkpoint. But now you realize it’s the local friendly mentally challenged kid your unit sometimes plays soccer with and the Taliban have strapped him full of explosives and told him to go hang out with his American friends because they have ice cream for him. So now here comes a naive, bomb laden 13 year old whose got a remote detonator some terrorist controls from an unknown location. Oh did I mention they have him holding his 1 year old little brother? To resolve this quickly, you need methods of problem solving. So this is where we will start talking about our initial step in reacting to situations you don’t have a specific solution to. Though this post will not reveal an entire problem solving paradigm taught to agents, it will give you one very useful method.

The first part of this three tiered approach is a mental stop. Three count pause. Remember, ideally you would have an instant reaction and SOP to act out so there would be no need for a pause, but circumstances have given you a situation that falls outside the scope of “if,then.” So despite the desire to act without hesitation, you recognize this is not something you are prepared for. So you mentally count to three. You then make a decision. Then you mentally pause again for five seconds. Then you either act on the decision or pivot to another decision and act. While 8 seconds is a lifetime in high stress situations, acting without thinking at all in a realm that you have no training in is worse. A very practical application of our 3 pause, 5 pause is interrogation. While many may believe that standard practice is to state nothing more than name, rank, and number, this is an impracticality that exists more in fantasy than reality. So, agents are taught to answer questions, just very carefully. You get asked something, you consciously pause for three counts, start a sentence, pause for 5 while continue considering further what to say, and then say it. Funny enough, pauses before answers make you seem more believable to interrogators. Also, if trained well enough in this process, even the influence of drugs and pain will enable you to carefully say your words. Really this is a good conversational practice anywhere as there are many people spouting off at the mouth without really thinking through what they say. Also, if you’ve ever met the “strong silent type”, consider if they really spoke less than everyone else or if they naturally just allowed a few moments to pass before answering or speaking. So now on to part two….

OODA loops. Really this is just a variation of the 3 pause, 5 pause but with a little more focus. OODA loop thinking will also lead us nicely into the final, most effective part of the techniques that follows. What is OODA? It stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. Developed decades ago by military man John Boyd, OODA has been proven effective in many combat arenas (actually documented to be used by fighter pilots in dog fights more than in the spy game). So let’s dive into using this. First of all, let’s Observe. This means shit hits the fan and you have to first of all, stop for a moment and literally observe. You need to figure out what is going wrong. Where is the gunfire coming from, who is here who is not supposed to be, what caused communication to suddenly stop, etc. You are focusing on abnormalities. Some useful tips: scan right to left (we read left to right and can fall into a subconscious pattern of “going through the motions” whereas move right to left improves our observation ability) and look for verticals that don’t match horizontals (most environmental scenes are either mostly full of vertical objects or horizontal objects. So if your in the Northeast part of the U.S. full of vertical trees, you would look for horizontal objects that are not naturally occurring). We want to avoid acting without have a complete enough picture on which to properly act upon. Now we need to Orient. The good news is you are on the second step to success on this four step loop. The bad news, this step is the sum total of you preparing various checklists, problem solving paradigms, or mental models well in advanced of you being in this situation. Let’s look at one or two to help you out though. We’ll utilize the simple concept of a 5 why problem solving model. Your goal is to find root cause of the crap that’s happening so we can act upon it. You’re taking fire from a rooftop across the street. Why? Because the enemy feels they have an advantage over you and suddenly feel brave. Why? Because your unit appears vulnerable to them. Why? Because they are in an elevated position with superior numbers. Why? Because the enemy was able to stage there without direct observation. Why? Because that building has a back ally that leads from an open field to a ladder that goes to the rooftop. Now it is quite possible that you won’t get all the way through all 5 whys given the pressure and limited time frame but the idea is to get to the root cause of what’s going on. Knowing that the enemy is using a particular route to move into firing positions is a little different from just shooting back at the muzzle flashes. Now we Decide. Here it is a matter of quickly determining the best course of action using all the information you have observed and deduced. Sticking with the rooftop fire example, you could decide to return suppressing fire and retreat to regroup or call in an artillery strike or circle behind the building to the field at the beginning of the enemy’s route or utilize suppressing fire and use precision point fire to pick the enemy off one by one from your current position. Once a decision is made, you must Act. This means moving with no hesitation to carry out the plan in a violent swift manner. No second guessing here. You may in fact have made the wrong decision but even a bad choice carried out with full commitment is better than a great choice done half-hardheartedly. Now it is this action, or rather the moment of pre-action that we get to our third dynamic: process simulation.

Process simulation. I’ve heard it referred to as mind loading, mental flashing, and dynamic visualization. No matter what the name, process simulation is so simple yet so effective. Essentially it is to always picture yourself doing the act you are about to do perfectly a split second before doing it. Now this is different than slow, meditative visualization you do in a relaxed state. This is a conscious effort to focus, while under stress, on executing. You’re about to take part in a life and death struggle, you might want to take that one second to flash a picture of your success to let your mind know the proper outcome. THIS SIMPLE TECHNIQUE MAKES A TREMENDOUS DIFFERENCE IN CARRYING OUT ACTIONS IN A HIGH STRESS SITUATION. The best operators and agents do this naturally. Ironically, so do the best athletes. Wrestling coaches have spoken about why some people can consistently take there opponents down while others with the same physical abilities and technique training cannot. It turns out that during the execution of the takedown, top wrestlers mentally flash an image of their success. This split second visualization aligns the mind and body as one and practically ensures optimal operation for at least a few moments. So whether you’re in a hand-to-hand fight to the death or about to do a door entry on a compound, use process simulation. Do it. Do it every single time you need to execute something in a highly intense situation. It will make a tremendous difference in outcome.

There you have it, Spycraft Tip and Trick #1: Let’s call this one, the Tactical Pause.

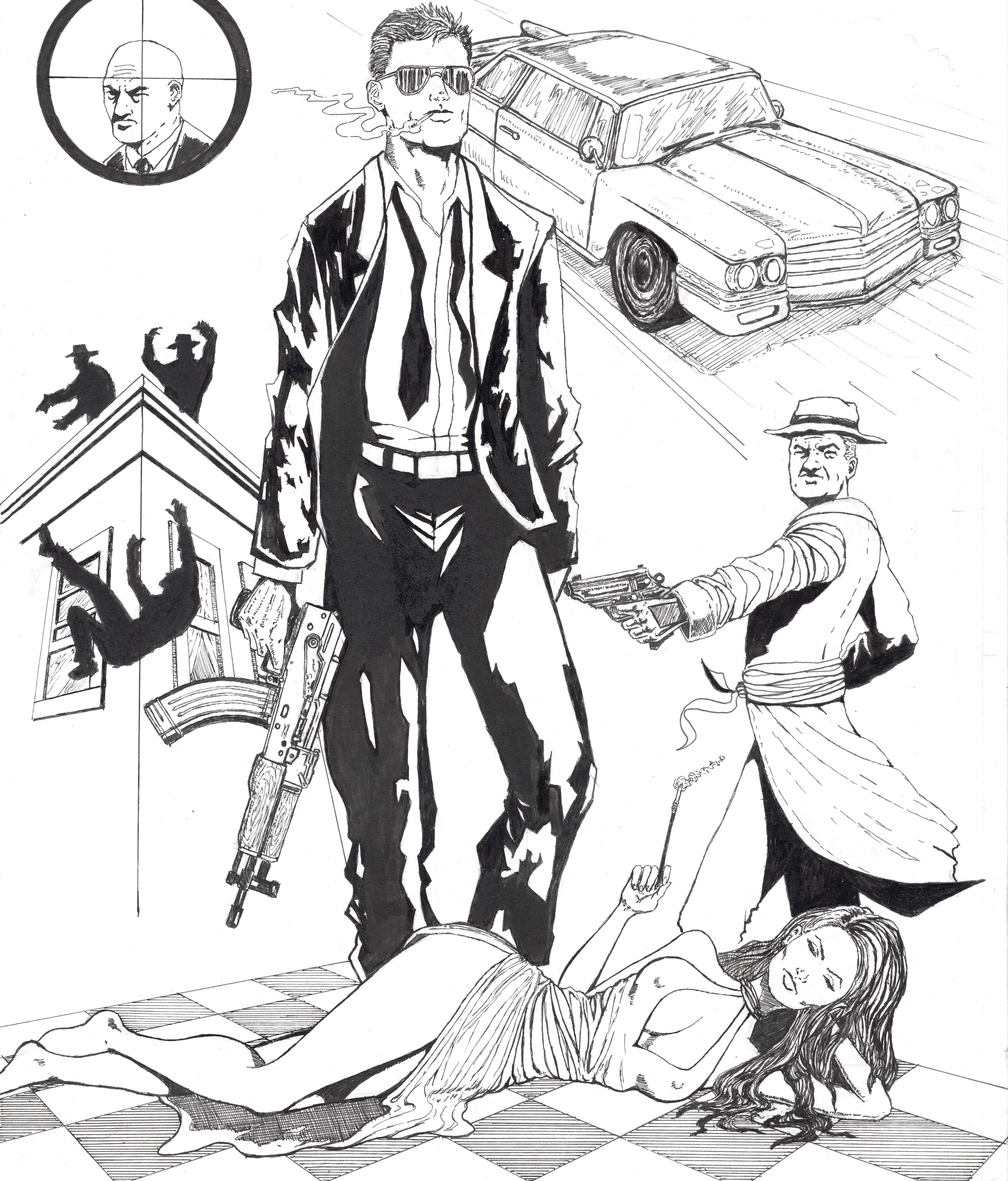

Keep an eye out for my upcoming graphic novel: Smoke, Drink, Spy (of course) that shows a fictionalized account of these concepts in action.